|

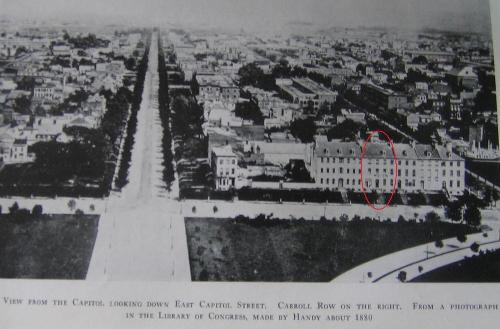

Ann Sprigg is buried in Range 53 Site 41 at Congressional Cemetery beside her mother, husband, and five children. Ann G. Thornton was born in Virginia about 1800. She married Benjamin Sprigg in 1818 and lived in Washington until her death in 1870. Benjamin was a clerk in the Office of the Clerk of the House and died in 1833. Left as the only provider for her family, Ann opened a boarding house on New Jersey Ave. south of the Capitol in 1834. In 1839 she relocated to a row of houses on 1st Street S.E., owned by Duff Green. The site is now occupied by the stairs to the Jefferson building of the Library of Congress. Ann's house was 4th from the corner of 1st and Pennsylvania Avenue, conveniently located just across the street from the U.S. Capitol. Her boarders were generally congressmen and lobbyists.

Benjamin was a slaveowner, with 8 slaves living in his house in the 1820 census. The 1840 census, 7 years after his death, shows that there were only free blacks living in Ann's home. There is as yet no direct evidence that Ann Sprigg actively participated in the URR, but her boarders were, if not aggressive anti-slavery radicals, at least sympathetic to the cause. James Brewer Stewart wrote in his essay in Antislavery Violence, "it seems inconceivable that abolitionist purists such as Theodore Weld or Joshua Leavitt would have permitted themselves to rent rooms from a serious slaveholder." Later he noted that she "seated her guests at a long table over which she presided." It is therefore equally inconceivable that Ann would, for such a long period of time, have surrounded herself with boarders who were so fiercely anti-slavery if she did not support their cause.

Theodore Weld, who stayed in the boarding house each time he was in Washington, wrote to his wife when he first arrived in Washington in 1842, "We speak on the subject of slavery with entire freedom, nobody gain-saying us. Mrs. Sprigg, our landlady, is a Virginian not a slaveholder, but hires slaves. She has eight servants all colored, 3 men, one boy and 4 women. All are free but 3 which she hires and these are buying themselves." On a subsequent visit he reported that "Mrs. Sprigg has now twenty five boarders, and here is a singular fact, and one that speaks well for Abolition in Washington - it is that for the last two years this has been known as the 'Abolition house': Giddings, Gates and Leavitt, abolitionists, and all the other boarders favorably inclined. … Mrs. Sprigg thinks it quite unsafe to have slaves in such close contact with Abolitionists, so she has taken care to get free colored servants in their places! Stick a pin there."

Ann's hired slaves escaped to the North on a regular basis - perhaps too regular. In December 1842, Weld wrote "You recollect that all the table waiters that were here last year have run away." Giddings writes of one escape in a letter to his son in August 1842: "Poor Robert who I believe was here when you visited us has left … He left on Monday evening some weeks since and the next he was heard from he was 'way up there in York State' full tilt for Canada. He left in company of some other very valuable chattels." (underscores are Giddings') Later it was established by another of Ann's employees, John Douglass, that Robert had been in the first group of slaves escorted to the north by William Smallwood. John Douglass took the "train" north shortly after Robert left.

Giddings knew of William Smallwood's URR activities, and it is therefore likely that Ann also knew. It is also likely that Ann assisted or at a minimum did nothing to prevent her hired slaves from joining the groups moving north. Boarding houses and hotels of the day were almost always staffed by slaves, so there was no need to provide secret rooms. Ann's house may well have been a "station" where slaves could "hide in plain sight" until it was time to leave. Weld's letters suggest that her boarders were very protective of Mrs. Sprigg, and it is likely that some of them, especially Giddings and Gates, acted on her behalf in making contact with UGRR representatives.

In January 1848, Ann's house was the scene of a kidnapping. Henry, a slave, and his wife Sylvia, free, were waiter and maid at Ann's house. Slave traders broke into the house and violently seized Henry and dragged him away to William's Slave Pen. Henry had raised $290 of the $350 he had agreed to pay his owner for his freedom when she sold him to the slave traders. With much effort on Giddings' part and finally with the aid of Duff Green (normally proslavery but believing this incident was bad publicity) arranged to purchase Henry's freedom. Duff Green was Sprigg's landlord, and it is likely that she played a role in convincing him to assist. Once free, Wilson returned to his position in Ann's house. This suggests that there was a strong bond between the Wilson's and Mrs. Sprigg, and it is therefore likely that Giddings' efforts to recover and free Henry were in part on Ann's behalf.

In 1848-49 Abraham Lincoln was one of Ann's boarders. Samuel Claggett Busey who was a boarder at that time wrote that "All the members of the House of Representatives were Whigs. … Mr. Lincoln, who may have been as radical as either of these gentlemen, but was so discreet in giving expression to his convictions on the slavery question as to avoid giving offense to anybody, …"

Sometime before 1860, Ann moved out of her boarding house, and during the war Carroll Row was used first to house contraband slaves and then supporters of the Confederacy. Mrs. Sprigg had fallen on hard times, but Clark Evans wrote in Cornucopia of Lincolniana, "Lincoln never forgot his former landlady, Ann Sprigg. In a July 21, 1864, letter to Treasury Secretary William P. Fessenden, the president recommended Sprigg for a position of clerk of the loan branch. He wrote, 'The bearer of this is a most estimable widow lady, at whose house I boarded many years ago when a member of Congress. She now is very needy; & any employment suitable to a lady could not be bestowed on a more worthy person." Ann was a clerk at the Treasury, living with her son, William Bowie, and daughter, Virginia, when she died in 1870.

|